The first in a two-part series.

“Light on one and heavy on the other” is more than a bartender passing judgment on two brands of beer.

The statement defines the U.S. government’s border control policy: Sporadic fencing along the Canadian border; a tough set of rules, a high fence and 1,200 National Guard troops (by August 1) along the Mexican border. The double standard is not lost on some Latinos, who are left to wonder whether the policy has become too personal: “Why Mexico and not Canada?”

The answer is fairly easy to discern, but somewhat difficult for some immigrants to digest.

While the U.S., Canada and Mexico belong to the trading triumvirate called NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), immigration is not one of the perks of the treaty. Mexicans fall in line for a visa and wait months to have it approved, just like any foreigner seeking to enter the U.S. Those with means enter as tourists or students, and those who cannot enter legally try the backdoor.

Meanwhile, an entirely different set of rules applies to Canada, America’s largest trading partner. As a “low risk” country, it has a cozy, visa-free arrangement with the U.S. The average Canadian citizen can show up at a port of entry with nothing but a valid passport, an ID card (usually a driver’s license), and a border crossing card. The need for a visa is waived for a limited time period, except for Canadian minors, fiancées and traders.

“NAFTA does not include immigration,” Cesar Romero, press attaché of the Mexican Consulate in New York, told FI2W. If the Canadians appear to enjoy preferential treatment, he said it’s not because of NAFTA. “It’s something else,” he said, and stopped there.

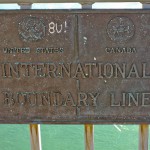

The 5,525-mile U.S.-Canadian border was practically non-existent for decades as the two countries enjoyed an “open and trusting relationship,” according to a study by the International Boundary Commission. Many towns shared libraries and opera houses, with neighbors able to walk across each other’s yard to cross the border without having to flash a passport or ID.

The post-9/11 era

But with the specter of 9/11 hanging dark and heavy over the U.S., Washington began a review of the northern border. What they found out were occasional incidents of drug and firearms smuggling, human trafficking, random violence, and unsuccessful terror attempts using the Canadian border.

To be fair, the Mexican border with almost 2,000 miles of concrete walls, mountain ranges, rivers and rickety fences winding from California to Texas, did not initially have an unsavory reputation. The aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican war of 1848 led to the annexation of other border states after Texas. Lots of jobs were available then, and Mexicans found work in American factories and farms, and in construction. By 2007, there were 29.2 million Hispanics of Mexican origin in the U.S., according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The Pew Hispanic Center said that of the estimated 12 million undocumented immigrants, more than half (55 percent) may be Mexican.

Drug and human smuggling along the Mexican border intensified over the years, straining the resources – as well as the friendship – of both countries. The U.S. has been pressuring Mexico to do more to contain narcotics smuggling and prosecute corrupt officials. Mexico insists trafficking wouldn’t flourish if the U.S. wasn’t such a profitable market for drugs. The U.S. estimates the business to be worth anywhere from $13.6 billion to $48.4 billion annually.

Frustrated by the lack of action from Washington, some Americans have taken up the Second Amendment option to arm themselves, fearful that crime would spill into their backyards. In response, Arizona passed a law making immigration – which is traditionally a federal concern — a matter for the local police. Under SB 1070, which takes effect July 29, cops will have the authority to question anyone they suspect is illegally in the country. Polls show many Americans support the law, which immigrant advocates fear may promote racial profiling.

“Yes, the cartel violence we are seeing in Mexico is not taking place in Canada, but there is human and drug smuggling that must be addressed,” Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano said in a 2009 speech before the Border Trade Alliance International Conference.

“We cannot pretend that there are no borders even though we have close, close relationships with Canada and with Mexico.”

She reported more than a million illegal persons have been arrested at the border in 2008, and 2.7 million pounds of narcotics were seized, making the control of illegal immigration “a priority.”

Queens College Professor of Sociology Andrew Beveridge, who tracks immigration trends, is aware of the double standard, but does not believe there is discrimination.

“I doubt that,” he said, noting that Americans value Mexico’s “hardworking immigrants.” He also said the Mexican population continues to increase.

While the approach to protecting the country’s northern and southern boundaries “will not be the same,” Homeland Security said policy will remain sensitive to the differences between Mexico and Canada – a policy that balances the time-honored tradition of friendship against the emerging threats.

Tomorrow, Ewa Kern-Jedrychowska of Nowy Dziennik/Polish Daily News reports on Polish immigrants who enter the U.S. illegally from Canada.