House for sale in Flushing, Queens

Single family in Colfax, Queens: $189,000, 4 BR, 3bath, Price reduced; contact agent

Despite a shaky real estate market, ads like this are still popping up on the Internet, tempting potential home buyers to bring out their calculators and start crunching the numbers: monthly payments vs. annual salary vs. closing costs vs. savings account.

In New York, Asian families, like many immigrants, view buying a house as a validation of their status as new Americans–and bona fide New Yorkers.

Many consider the city a place where anyone who embraces hard work, has lots of drive and even more daring can own a home. So when the housing market came crashing down, Asian Americans found themselves among the stunned casualties.

This recession, the worst since the Great Depression of 1929, has resulted in a staggering job losses across the country. Asians are among those who thought they were secure in industries such as technology, health and media, but found themselves losing not only their jobs but also their homes.

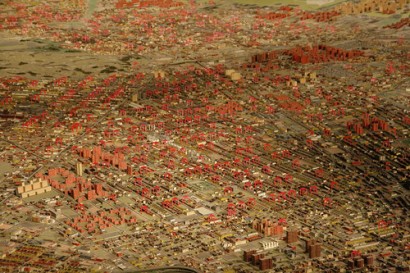

Panorama of New York City at the Queens Museum of Art. The pink triangles represent blocks with 3 or more foreclosures. (Photo: Sarah Kramer)

Loan modification cases and defaults are up in Queens, the borough that leads the city in foreclosures. Queens is also home to thousands of Asian immigrants. In the neighborhoods of Jackson Heights, Jamaica and Richmond Hill, South Asians, in particular, are starting to feel the burden of unpaid mortgages.

“We did some research,” said Seema Agnani Executive Director of Chhaya, a housing support and advocacy group catering to South Asians. “As many as 50 percent of total defaults in some Queens neighborhoods are South Asians.”

In 2009, Chhaya provided foreclosure prevention counseling to about 100 families, and was able to help about 20 percent of them receive favorable loan modifications, including a Mr. Rashid (who declined to give his first name). He had a troublesome Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) mortgage and was struggling to make payments.

“We helped him get his loan modified,” said Shan Rehman, Communications Associate for Chhaya.

Chhaya is aiding working men and women, like livery cab drivers, construction workers and small business owners negotiate their loan modifications—or in the worst cases, navigate the trail to foreclosure. This has become common among South Asians from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, said Agnani.

“For those who come to us early enough, we were able to assist them negotiate with their lenders,” Agnani said. “Unfortunately, a lot of them wait until they’re six months behind in their mortgage.”

But she said prospective home buyers are now becoming more informed about predatory lending tactics by mortgage lenders. “We tell them about tactics mortgage companies use to aggressively push their products.”

She also tells them the American Dream is still possible, but that there are lessons to be learned from the current crisis: Don’t rush, and only buy when you’re ready. She says some immigrants make the quick leap from renters to homeowners without a solid financial buffer, relying solely on their current employment.

Korean American homeowners in Queens are also reeling from the housing crisis and the economic recession.

“We advised and counseled more than 50 homeowners in a six-month period, submitted 13 loan modifications, and secured three three-month trial modifications under the Obama Administration’s Making Home Affordable Program,” said Zena Kim, foreclosure prevention counselor at MinKwon Center for Community Action.

Among the 50 homeowners the MinKwon Center worked with over the past six months, about 10 are still struggling through an active foreclosure proceeding, Kim said.

“Most of these homeowners are small business owners whose businesses have been negatively impacted by the recession, making it difficult for them to stay current on their mortgages. Majority of them have been at least three months in arrears.” Many live in Queens’ Flushing neighborhood.

At a recent foreclosure workshop Kim conducted in partnership with Queens Legal Services, 10 homeowners attended, and another 10 homeowners responded to media reports afterward.

“In March alone, we had at least 20 homeowners call MinKwon in a one-month period to discuss their financial hardships,” she said. “The more outreach is conducted, the more we find out that Korean American homeowners are struggling severely.”

Kim said they’ve also seen a “good concentration” of foreclosure cases in Nassau county and Suffolk county. “We have assisted clients from all parts of New York State,” she said.

On the day of the interview for this article, Kim was reviewing files for five clients applying for a loan modification.

Bankruptcy and foreclosures touch nearly all Asian communities

“There are some who can’t pay their [subprime] loans anymore since the economy got worse,” Chiaki Torisu of the Japanese American Social Services Inc. said. For Japanese immigrants with troubled loans, she said Jassi offers information and referrals. “We don’t have a lawyer, but we have a referral system that may be able to help them.”

The city’s Chinese community has not been excluded from the housing market crisis either.

“It’s a major concern,” said Ester Wang, project coordinator for Chinatown Justice Project, a program of the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence. While Chinatown’s marginalized renters are the main focus of CJP, Wang said rising mortgage payments and foreclosures are “a piece of a broader crisis that is affecting us also.”

“It’s an issue our members talk a lot about,” she said.

The Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), another housing advocacy group for Chinese immigrants, said foreclosures aren’t just a problem for homeowners, tenants are also affected.

“What if the landlord files for foreclosure?” asked Mae Lee, director of CPA.

But many Asian Americans find it difficult to ask for help with their finances. Cultural “shame” or “loss of face” may discourage some from making public a very personal problem, such as losing one’s house.

“They’re afraid to talk about it, there’s some ego involved, some shame,” Agnani said. “Some don’t want to admit they have problems.” In some cases, she said, it is the women who initiated the contact, indicating some reluctance from the husbands to seek help.

“Some are embarrassed,” said Agnani. They would rather turn to family than seek help from the government.