Andrea Tejeda, 26, feeds her 4-year-old daughter, Jadieliz Padilla. Limited food and cooking facilities are available in a Manhattan hotel where they are living. Photo: Maite H. Mateo

The terrifying message came via a robo-call: April 20 is your last day at the hotel.

“Pack your things. Your stay is not the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) responsibility anymore,” Andrea Tejeda, 26, recalls hearing on her cellphone.

Hours later she received a text message from NYC’s Department of Homeless Services saying that it didn’t have anywhere for her and her 4-year-old daughter, Jadieliz Padilla, to go.

Of the 12 Puerto Rican families staying at a hotel on West 38th Street in Manhattan, five received the same message. All of them have young children. “We got desperate,” Tejeda said. “We didn’t know what to do.”

The following day, she joined about 50 people rallying on the steps of City Hall, protesting their imminent eviction. Later that day Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city would cover the cost of the hotels for evacuees from Hurricane Maria until May 14.

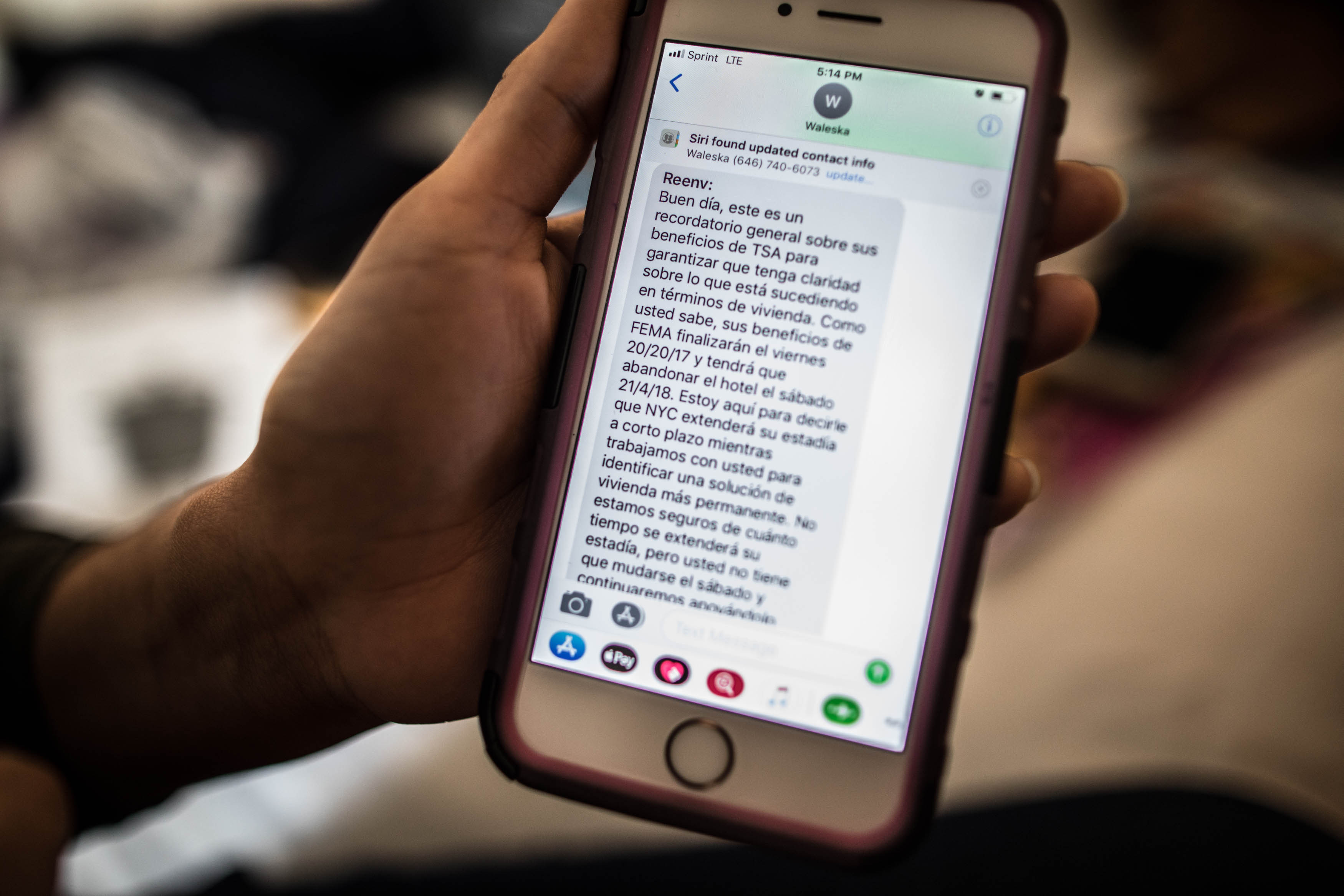

Andrea Tejeda received a text from FEMA giving her only days notice to leave the hotel; photo: Maite H. Mateo

FEMA subsequently stepped in and resumed paying the bill. But even after FEMA extended the deadline to June 30, the fate of Tejeda, her daughter and the 136 other Puerto Rican families currently staying in hotels in New York State is uncertain. The only thing they’ve been told is that FEMA is offering tickets to fly them back to storm-ravaged Puerto Rico.

“I feel in limbo because every time I go ask for help, they never want to help,” Tejeda said.

Her frustration is shared by many evacuees who are trying to navigate the bureaucracy as they look for a place to stay, a job, schooling for their children or health care.

The New York Disaster Interfaith Services (NYDIS), a nonprofit group that worked at the city’s Hurricane Relief Center, estimates there are still some 10,000 evacuees from Maria living in New York City. While many are staying with relatives, others have gone to city shelters. Peter B. Gudaitis, CEO of NYDIS is calling on the state and city governments to do more to coordinate relief groups’ assistance and to help the displaced find jobs.

“FEMA has fallen short when it comes to planning for and responding for diaspora events in the United States,” Gudaitis said.

Gudaitis says Puerto Rican evacuees also face steep challenges because many lack English language skills. A large number are senior citizens in poor health.

For Tejeda, trying to survive in New York City is a daily struggle. She receives $352 a month from the city to spend on food, but she’s been skipping lunch because she can’t cook in the hotel and food at nearby restaurants is expensive. She said she often eats nothing until a dinner of rice with ketchup and canned sausage.

After June 30 when FEMA stops providing temporary accommodation, she thinks she will have to try to go to a shelter. But Tejeda is concerned a shelter can’t accommodate them. “As they say, there is no space for us there, I don’t know what’s going to happen,” she said. “I can’t be on the street with a 4-year-old.”

Her goal is to find an apartment so she can have a stable and safe life. But while she is in the FEMA hotel, she is not eligible for a rent voucher, which makes planning for longer term housing a challenge. “I want FEMA to let me go and the government to give me a push so I can move forward, find a stable job and raise my daughter.”

“There is definitely a feeling that we have to hope for the best, but now we have to prepare for the worst,” said Luz Correa, chair of the Bronx Coalition Supporting Hurricane Maria Evacuees. She has been in touch with families at the hotels and said some are preparing to enter the city’s shelter system. Placement isn’t guaranteed, though. A spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office said it “will continue creating strategies to support case management for these families affected by Hurricane Maria,” but didn’t provide details.

The city wouldn’t reveal how many Puerto Rican families displaced by Maria are currently in shelters. Officials did say the city’s Hurricane Relief Center processed 2,521 families and made 945 referrals to HomeBase, which oversees the city’s homeless prevention strategy. It was unclear, though, how many of those referrals led to shelter.

In the weeks immediately following Hurricane Maria, the NYC government tried to dissuade evacuees from settling in the city. At an October 12 news conference Mayor de Blasio said the city didn’t have a housing plan for Puerto Rican hurricane evacuees, although he promised education and health services. “I don’t want to encourage people to come here if they don’t have some family to turn to,” he said. “We have to be really clear about that. This is a city that’s ready to do anything and everything for people that come here, but we are also clear that we have tremendous strains we are dealing with right now, and housing is our number one.”

Victor Martinez, founder of Diaspora Por Puerto Rico, a community-based organization that sprang up after Maria, acknowledged, “there are a lot of homeless in the city, but this is also an issue that should be attended to.”

Martinez describes evacuees’ experiences as an emotional rollercoaster as they search for housing and services. In addition to the emotional impact, the lack of housing impedes their ability to get jobs, access education, and medical services.

4-year-old daughter, Jadieliz Padilla plays with her doll in their hotel room; photo: Maite H. Mateo

Tejeda has been bouncing from place to place since arriving in New York City from San Juan on December 14. Initially, she stayed in her uncle’s two-bedroom apartment for two months, then she moved to a shelter in Manhattan which she says was infested with rats and cockroaches. On March 3rd, FEMA offered her a space at the hotel in Midtown Manhattan.

Coming to New York wasn’t an easy decision. But she felt compelled to leave Puerto Rico after her four-year-old daughter witnessed a murder while they were staying at her mother’s home in San Juan. That came a year after the slaying of Tejeda’s ex-husband.

While Tejeda’s main concern is safety, Barbara Pena, a mother of two, one with special needs, came not just for housing security but also the support she needs for her children. Recently she gave up trying to live in New York City and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts. “I couldn’t deal with [the uncertainty] anymore,” she said. “I wouldn’t go back to a shelter. I’d have to go to the streets.”

In Springfield, her rent voucher from Puerto Rico was accepted. She is living in a FEMA hotel while she raises money to pay a security deposit on a rental. “In New York, I couldn’t find anything with my voucher because the rent is too expensive,” she said.

Nonprofits like Diaspora Por Puerto Rico, the Bronx Coalition and New York Disaster Interfaith Services have been trying to connect evacuees with the social services available to them. In March evacuees met at Hostos Community College with representatives of city agencies, food pantries, and medical nonprofits.

When the April 20 deadline was approaching, the groups helped organize the City Hall demonstration. They also planned to open an emergency shelter to give evacuees time to decide whether to stay in New York City or go back to Puerto Rico.

Beyond losing their homes and possessions, many families feel they cannot rebuild their lives in Puerto Rico because of the slow recovery from the September storm. Power outages continue across the island and officials recently announced plans to permanently close 266 schools.

At the end of April, Gov. Andrew Cuomo launched the New York Stands With Puerto Rico Recovery and Rebuilding Initiative. Construction workers and about 500 students from the State University of New York and the City University of New York will be deployed by early June for two to four weeks to help rebuild homes and infrastructure on the island. The 2018 hurricane season officially started on June 1.

Gudaitis, from New York Disaster Interfaith Services doesn’t see this plan as a solution. He said it is probably cheaper to fly Puerto Ricans home and help them rebuild than absorb them into New York’s economy. “The problem with that is that Puerto Rico’s economy is no better today than it was a year ago – it’s worse,” he said.

Tejeda’s salary as a clothing vendor in San Juan decreased after the hurricane from $320 a week to $130 because the store was rotating employees to make sure everybody would be paid as business sagged. On May 8, she got a part-time job as a college assistant for $7.25 an hour in Queens. She said it would take her more than a month to save up for a deposit on an apartment.

In San Juan she lived in a two-bedroom apartment on the 20th floor and could see the ocean from her balcony. The hurricane broke all the windows and flooded her home. Her furniture, clothes and her daughter’s toys were destroyed by mold and none of the apartments in Tejeda’s government-owned building have been repaired.

Even though housing in New York City is proving to be more of a struggle than she imagined it would be, Tejeda, who has a degree in criminal justice, feels that going back is not an option.

She wants to stay and become a police officer. “I want to study here,” Tejeda said. “I want to make progress here and give my daughter a good life.”

Fi2W is supported by the David and Katherine Moore Family Foundation, the Ralph E. Odgen Foundation, the J.M. Kaplan Fund, an anonymous donor and readers like you.