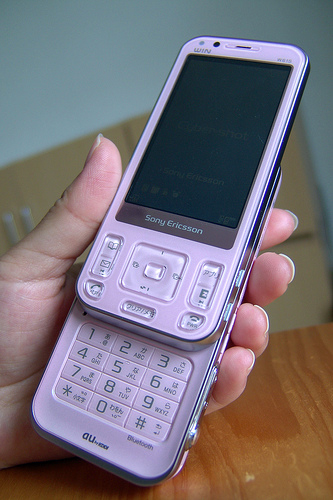

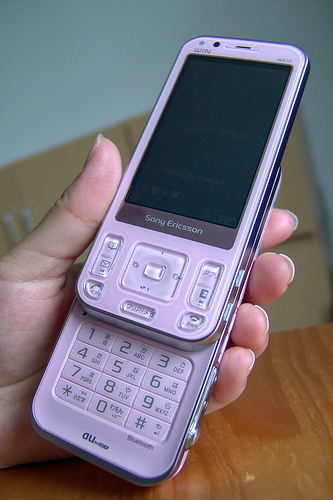

Immigrants are using their cellphones to upload stories to Mobile Voices. (Photo: MJTR/Flickr)

Every day Maria De Lourdes Gonzalez jumps on a bus on the way to work. She cleans houses for a living, but the rest of the time she’s telling stories about the people she meets on the bus.

“Si salgo a la calle, me pesco una historia y la agarro,” she says in Spanish. “If I go out to the street I catch a story and I grab it.”

Madelou, as friends like to call her, has been telling stories for the past two years through Mobile Voices (Voces Moviles), an online multimedia platform that allows her to upload video, pictures, text and sound with a few clicks on her cellphone.

The initiative was created by day laborers, household workers, the University of Southern California, Drupal software Programmers and the Institute of Popular Education of Southern California (IDEPSCA). The program provides a virtual space for low-income people, particularly immigrant workers, to share their personal stories or those of others they encounter in their community.

Madelou, 64, grew up on the periphery of Mexico City. As she raised her three children there was one line she always repeated. Perhaps too much, she admits.

“I always have this idea with me, that being born in a difficult economic situation—and I said to my children—it’s different than saying that we grew up very poor,” she said in Spanish, using the word “pobresito” that is a diminutive of poor. “It’s not a synonym for saying that we are dumb, or stupid. It’s just that some are in a circumstance of advantage and others of disadvantage. We have to do everything we can to abandon a situation of misery.”

That’s how she approaches the stories she’s made for Mobile Voices. Her focus has always been “Manos que Trabajan,” which translates to “Working Hands.” Part of her project has literally been posting pictures of the hands of laborers, from farm-workers to seamstresses.

Some people say that immigrants and low-income workers need others to facilitate their voice being heard. But Madelou likes to look at it differently. She says immigrants and household workers like her have a voice and they are eager to express it when the opportunity arises.

“If they don’t want to see us at least we can tell them: “Yes, we are invisible. But we are the hands that work.”

One of the founders of the program, Amanda Garcés, technology development outreach coordinator and former day laborer organizer at IDEPSCA, says she sees Mobile Voices “as a window to all the communities that have a voice but have been silenced.”

The group continues to grow and this month it won “Best Mobile Content” in the World Summit Award in Abu Dhabi, in the category of m-inclusion and empowerment. The World Summit Award is part of a project created by the United Nations in partnership with governments, civil society and other non-governmental organizations. Its goal is to end poverty, hunger, and disease, through providing access to information and communications technology.

The category in which Mobile Voices won pertains “to reducing the ‘digital divide’ between technology-empowered and technology-excluded communities, such as groups in rural areas, women, senior citizens, disabled citizens and children” according to the World Summit Award website.

In light of the negative images of day laborers often portrayed in the media or by anti-illegal-immigration organizations, Mobile Voices started working with day laborers who attend the six centers run by IDEPSCA.

“Mobile Voices’ platform was designed around the communities and their realities. We all have a cellphone,” said Pedro Espinoza, 23, a community organizer with IDEPSCA.

Through the program, cellphones have now become an item in the day-laborer tool-belt, Espinoza explained. For example, they can be used to document abuse that might be going on.

(Mobile Voices has a policy of not asking people whether they have legal status or not. And if people volunteer that information during interviews, they usually won’t post a picture of the individual.)

But being part of Mobile Voices is more than just trying to document injustice. Garcés describes it as an experience in which all the participants teach each other, be it through the different features they can use on the phone or how to tell a story.

“When a worker learns how to navigate the site, it’s also learning how to navigate the Internet,” said Espinoza. “They are empowered through it.”.

Ranferi Velazquez, 53, is a Guatemalan day laborer who has been a part of Mobile Voices for two years. He says he uses the project to tell people about his life.

“I make reference to my experiences in the Guatemalan military—I used to parachute,” said Ranferi. “I work as a day laborer and I like [Mobile Voices] because it has allowed me to express what we do as Hispanics to make this country greater.”

Ranferi also likes to post blogs and images about gardening and different ways of preserving resources like water and electricity.

Crispin Jiménez, 64, another day laborer originally from Zacatecas, México, hopes to show a different face of day laborers on the Internet.

“The Minuteman try to paint us as if we were third-class citizens that should be in our countries, when this country was built on immigrants. We are showing a real face, we are not robbers, we come here to make the economy grow as much as ourselves,” he said.

Madelou never runs into the people she meets on the bus again, but their stories always linger in her memory and have traveled around the world through the Internet.

She has created over 615 stories for Mobile Voices. Some are written, others involve pictures or just recorded sound that she uploads quickly to the website from her cellphone. Through workshops, she’s learned to use the Internet, and also video editing programs to assemble footage. Among the murmur of voices, there’s one she remembers clearly.

It’s the story of Jaqueline Rivera, a woman who sleeps in a closet and left her children so she could come to the U.S. and give them a better life. This is how Madelou wrote Jacqueline’s story:

A strong woman…Very strong! Facing the emotional turmoil of being separated from her children for the desire of a better future. How many more woman like Jaqueline Rivera can be added to this desire, to this human right for a better life for your love ones? (How many can be added?) to the whisper of this voice, to the endless choir of all the whispers (that say): “Legalization!”

Feet in Two Worlds is supported by the New York Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation with additional support from the Mertz Gilmore Foundation.